About 40% of all abortions in the U.S. are now done through medication — rather than surgery — and that option has become all the more pivotal during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Abortion rights advocates say the pandemic has demonstrated the value of medical care provided virtually, including the privacy and convenience of abortions taking place in a woman's home, instead of a clinic. Abortion opponents, worried the method will become increasingly prevalent, are pushing legislation in several Republican-led states to restrict it and in some cases, ban providers from prescribing abortion medication via telemedicine.

Ohio enacted a ban this year, proposing felony charges for doctors who violate it. The law was set to take effect next week, but a judge has temporarily blocked it in response to a Planned Parenthood lawsuit.

In Montana, Republican Gov. Greg Gianforte is expected to sign a ban on telemedicine abortions. The measure’s sponsor, Rep. Sharon Greef, has called medication abortions “the Wild West of the abortion industry” and says the drugs should be taken under close supervision of medical professionals, “not as part of a do-it-yourself abortion far from a clinic or hospital.”

Opponents of the bans say telemedicine abortions are safe, and outlawing them would have a disproportionate effect on rural residents who face long drives to the nearest abortion clinic.

“When we look at what state legislatures are doing, it becomes clear there’s no medical basis for these restrictions,” said Elisabeth Smith, chief counsel for state policy and advocacy with the Center for Reproductive Rights. “They’re only meant to make it more difficult to access this incredibly safe medication and sow doubt into the relationship between patients and providers.”

Other legislation has sought to outlaw delivery of abortion pills by mail, shorten the 10-week window in which the method is allowed, and require doctors to tell women undergoing drug-induced abortions that the process can be reversed midway through — a claim that critics say is not backed by science.

It's part of a broader wave of anti-abortion measures numerous states are considering this year, including some that would ban nearly all abortions. The bills' supporters hope the U.S. Supreme Court, now with a 6-3 conservative majority, might be open to overturning or weakening the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision that established the nationwide right to end pregnancies.

Legislation targeting medication abortion was inspired in part by developments during the pandemic, when the Food and Drug Administration — under federal court order — eased restrictions on abortion pills so they could be sent by mail. A requirement for women to pick them up in person is back, but abortion opponents worry the Biden administration will end those restrictions permanently. Abortion-rights groups are urging that step.

With the rules lifted in December, Planned Parenthood in the St. Louis region would mail pills for telemedicine abortions overseen by its health center in Fairview Heights, Illinois.

A single mother from Cairo, Illinois, more than a two-hour drive from the clinic, chose that option. She learned she was pregnant just a few months after giving birth to her second child.

“It wouldn’t have been a good situation to bring another child into the world,” said the 32-year-old woman, who spoke on the condition her name not be used to protect her family’s privacy.

“The fact that I could do it in the comfort of my own home was a good feeling,” she added.

She was relieved to avoid a lengthy trip and grateful for the clinic employee who talked her through the procedure.

“I didn’t feel alone,” she said. “I felt safe.”

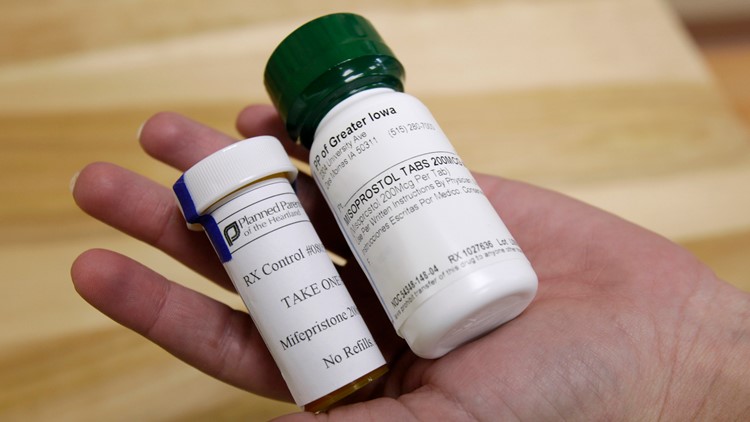

Medication abortion has been available in the United States since 2000, when the FDA approved the use of mifepristone. Taken with misoprostol, it constitutes the so-called abortion pill.

The method’s popularity has grown steadily. The Guttmacher Institute, a research organization that supports abortion rights, estimates that it accounts for about 40% of all abortions in the U.S. and 60% of those taking place up to 10 weeks’ gestation.

“Beyond its exceptionally safe and effective track record, what makes medication abortion so significant is how convenient and private it can be,” said Megan Donovan, Guttmacher’s senior policy manager. “That’s exactly why it is still subject to onerous restrictions.”

Planned Parenthood of Southwest Ohio, which includes Cincinnati, says medication abortions account for a quarter of the abortions it provides. Of its 1,558 medication abortions in the past year, only 9% were done via telemedicine, but the organization’s president, Kersha Deibel, said that option is important for many economically disadvantaged women and those in rural areas.

Mike Gonidakis, president of Ohio Right to Life, countered that “no woman deserves to be subjected to the gruesome process of a chemical abortion potentially hours away from the physician who prescribed her the drugs. ”

In Montana, where Planned Parenthood operates five of the state's seven abortion clinics, 75% of abortions are done through medication — a huge change from 10 years ago.

Martha Stahl, president of Planned Parenthood of Montana, says the pandemic — which increased reliance on telemedicine — has contributed to the rise in the proportion of medication abortions.

In the vast state, home to rural communities and seven Native American reservations, many women live more than a five-hour drive from the nearest abortion clinic. For them, access to telemedicine can be significant.

Greef, who sponsored the ban on telemedicine abortions, said the measure would ensure providers can watch for signs of domestic abuse or sex trafficking as they care for patients in person.

Yet advocates of the telemedicine method say patients are grateful for the convenience and privacy.

“Some are in a bad relationship or victim of domestic violence,” said Christina Theriault, a nurse practitioner for Maine Family Planning who can perform abortions under state law. “With telemedicine, they can do it without their partner knowing. There’s a lot of relief from them.”

The group has health centers in far northern Maine where women can get abortion pills and take them at home under the supervision of health providers communicating by phone or videoconferencing. It spares women a drive of three to four hours to the nearest abortion clinic in Bangor, Theriault said.

Maine Family Planning is among a small group of providers participating in an FDA-approved research program allowing women to receive the abortion pill by mail after video consultations. Under the program, the Maine group also can mail pills to women in New York and Massachusetts.